Laurisilva: The Misty Forest

Juan Luis Arsuaga (Madrid, 1954) fondly recalls his first journey to the Canary Islands, eagerly asking, “Where is the laurisilva? I want to see the laurisilva!” These misty forests, remnants of eight million years ago and extinct in Europe, can still be enjoyed in Anaga (Tenerife) and the Garajonay National Park in La Gomera (pictured), where trees collect fog droplets brought by the trade winds, seemingly milking water-laden clouds. While vestiges of this primeval laurisilva also exist in the Iberian Peninsula, as noted by the paleontologist, he has always been fascinated by the succession of landscapes that have depicted human evolution over millions of years: from laurels, strawberry trees, and the lush forests of Extremadura to the so-called “canutos” of Cádiz, gallery forests where ferns thrive.

Rain and Darkness in the African Tropical Belt

“We come from the jungle,” Arsuaga repeats several times during a phone conversation that unfolds in two settings: while he is in a bookstore in Valencia and, days later, strolling through a street in Madrid. Specifically, we come from the rainy African jungle, within the tropical belt of that continent. It’s a landscape he loves, although its main characteristic, as he emphasizes, is the lack of light reaching the ground. In this rainforest, “dark as a cave,” the ardipithecus (a genus of hominid) lived between seven and four million years ago.

The Australopithecus Gazes Upon the Savannah

About four million years ago, the australopithecus took the leap and ventured out of the darkness of the jungle into the brighter expanses of the savannah. But it wasn’t the vast herbaceous plains where safaris are organized, allowing one to view the entire area from a car, akin to the Serengeti. Arsuaga jests, “I see depictions of the poor australopithecus in the herbaceous savannah and I feel like saying, ‘What are you doing there? Have you lost your way? Get out of there, man, you’re going to get eaten by predators!'” To traverse these prairies, they would have needed horses, which came later. The wooded savannah landscape these ancestors saw was more akin to Gombe Stream National Park in Tanzania (where Jane Goodall researched chimpanzee behavior) or Pilanesberg Game Reserve in South Africa (pictured). “These are less touristy spaces because you don’t see as much,” he points out.

The Mediterranean Forest as a Gateway to Eurasia

The highly touristy and open Cabañeros National Park (northwest of Ciudad Real and southwest of Toledo), dubbed “the Spanish Serengeti,” could serve as a good example of the Mediterranean forest traversed by Homo antecessor one and a half million years ago. “The vegetation has changed much less than the fauna; at that time, there were lions and elephants in the area,” notes the paleontologist, who hosts the radio show ‘The Pleasure of Admiring’ on RNE, where he takes listeners on a journey through biomes (sets of ecosystems similar in climate, flora, and fauna) that Homo sapiens and their ancestors have trodden, from jungle to tundra.

A Journey Northward into Europe

Arsuaga suggests that heading northward, as Homo heidelbergensis did half a million years ago during its expansion across Europe, is akin to ascending a mountain in terms of encountering vegetation zones: Mediterranean, deciduous, pine, taiga, or tundra. Thus, our ancestors progressed from the Atlantic forest in Cantabria to the mixed forests of central Europe, and finally to coniferous forests in Sweden or Finland. As notable landscapes, the paleontologist favors two mixed forests: Białowieża Forest, straddling Poland and Belarus, the last refuge of the European bison; and, provocatively, Chernobyl: “Today, the largest natural area in the Old Continent,” due to the noteworthy absence of human inhabitants.

The Steppe-Tundra of the Last Ice Age

Fifty thousand years ago, the planet experienced its last ice age, and things got tough for Neanderthals, already living in Europe, and for Homo sapiens, who were beginning to arrive. It was bitterly cold, with vast glaciers dominating the landscape. Our ancestors survived as best they could in tundra and steppe landscapes, where woolly mammoths, woolly rhinoceroses, and reindeer coexisted with antelopes, horses, or bison. The steppe-tundra is an arid landscape of mosses, lichens, grasses, and low shrubs, devoid of trees, reminiscent of the Gobi Desert in Mongolia.

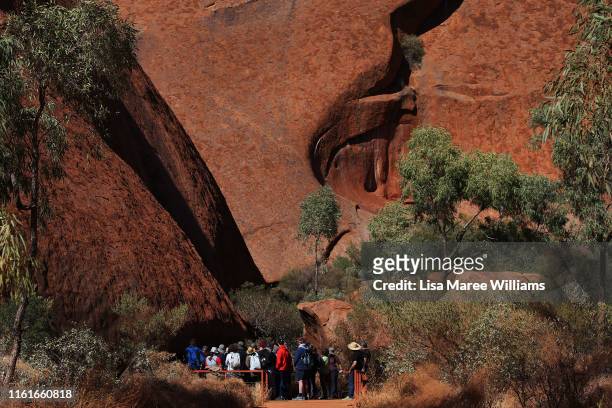

The Expansion into Australia

The arrival in Australia is perhaps one of the lesser-known milestones of human expansion. It is believed to have occurred some 40,000 to 50,000 years ago, with settlers arriving by boats from present-day Indonesia, taking advantage of the fact that during the last ice age, the sea level was much lower, and Australia and New Guinea formed a single continent, called Sahul. Once ashore, they witnessed landscapes like those of Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park (pictured), with its impressive geological formations in central Australia, a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1987. Some researchers argue that the vast grasslands and the predominance of fire-resistant eucalyptus and acacias could be the result of fires set by these early prehistoric settlers.

America, from End to End

The major expansion into America dates back some 13,000 years, with the representative landscape being the Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego regions (Argentina and Chile) at the southern tip of the continent. “In Africa and Eurasia, we co-evolved with fauna, and that’s why megafauna still exist there,” explains Arsuaga. However, in Australia and America, elephants, mammoths, and giant sloths lived, which became extinct coinciding with the arrival of humans; also with climate change, as we are at the end of the ice age. “I believe everything played a role, but it was the humans,” argues the paleontologist who, in 2014, curated, alongside naturalist Carlos de Hita, an exhibition of the soundscape that has accompanied us since our beginnings. “It was probably the only exhibition in history that took place with the lights off,” he says very seriously.

Humanity Populates Easter Island

During the European Middle Ages (5th to 15th centuries), Hawaii and other Polynesian islands in the Pacific were gradually settled. Easter Island, with its triangular shape, volcanoes, rugged coastline, and imposing moai statues, was the last territory on the planet to be colonized. It has been part of Chile since the 19th century. “Only Antarctica remains uninhabited,” Arsuaga points out.

The Current Landscape

Arsuaga concludes his journey through the stages of evolution with a new landscape, created by humans, anthropized, “but no less valuable for that.” Such as the cereal steppe of the Castilian fields. He calls

for the protection and defense of these historical, albeit artificial, enclaves rich in life—partridges, hares, harriers—and cultural values, which began to take shape in the Neolithic era with the adoption of animal husbandry and agriculture.

Bonus: The Moon

“The Moon is a landscape, and moreover, the last frontier crossed by humanity, right? So let’s include it; it’s part of the evolution of our species,” suggests Arsuaga. On July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong, commander of Apollo 11, the fifth manned mission of the United States Apollo program, set foot on the surface of the Earth’s only satellite, south of the Sea of Tranquility. His famous words (“That’s one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind”) could well serve as the culmination of this photogallery.