Pinpointing the exact origins of the Y2K revival trend is akin to chasing elusive shadows through the corridors of time. There exists no precise moment, no unanimous agreement among scholars or enthusiasts. Perhaps it sprang forth from the viral campaign advocating for Britney Spears’ emancipation or Paris Hilton’s Netflix cooking show. It could have been triggered by the reboot of the teenage classic “Gossip Girl” or the reruns of “The O.C.” on HBO Max. The announcement of the third installment of “Legally Blonde” or the fifth “Scream” film might have played a role. It could even be traced back to the resurgence of Bennifer or the comedic sketch on “Saturday Night Live” by Kim Kardashian, referencing the infamous sex tape that propelled her to fame. Even Olivia Rodrigo’s “Brutal” music video, where she dons the same Roberto Cavalli minidress worn by Britney at the 2003 American Music Awards, could be considered a catalyst. Suffice it to say, there were plenty of catalysts for this cultural resurgence.

Scholars of this phenomenon trace its beginnings to the early months of 2020, coinciding with the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, while others point to a second wave in 2021, fueled by its commercial potential. Some even harken back to 2014, when the term gained new significance. It emerged on Tumblr, a once-popular microblogging platform, initially referencing a flood of images featuring Bratz dolls, pink flip phones, bling-bling accessories, and GIFs from movies like “Mean Girls” and “Jennifer’s Body.” Teenagers shared memories of their not-so-distant childhoods, tagging their posts with #Y2K, a nod to the acronym for “year two thousand,” evoking the Y2K computer virus that threatened to disrupt the new millennium. Today, the hashtag garners around 500 million views on TikTok and serves as a major draw on platforms like Depop, a marketplace with 30 million users, 90% of whom are under 26. Yet, there remains uncertainty about when this fervor for the early 2000s will wane.

The Fashion Phenomenon: A Journey Through the Early 2000s Aesthetic

For at least the past couple of years, the aesthetic of the early 2000s has permeated collections across the spectrum, from luxury prêt-à-porter to mass-market chains. This resurgence is endorsed by a generation of creators who champion the validity of their youthful memories. French designer Olivier Rousteing, at 36, posed a rhetorical question while presenting his spring-summer 2020 collection for Balmain: “Is nostalgia for our early 2000s childhood culture any less cool than the more widely accepted fixation on the seventies and eighties?” It was a question implicitly answered by the business world: there’s no such thing as bad nostalgia when it comes to financial success, especially in tumultuous times.

“Insecure about the future, fashion seeks solace in its past. This phenomenon always occurs during periods of global crisis, such as a pandemic,” explains Andrew Groves, a Design professor at the University of Westminster in London. For the fashion industry, the Y2K fever may merely represent another asset in the so-called economy of nostalgia. However, for the centennial youth, reminiscing about the early 2000s primarily serves as a coping mechanism, providing solace and familiarity amidst the oppressive reality of the post-pandemic world. In a society no longer able to afford the blatant superficiality of the past, the distant cultural references of the early 2000s strangely feel like home. The challenge now is not to let this surge of nostalgia become another problem in itself.

Blumarine’s Bold Revival: A Controversial Resurgence

“More daring, more provocative, more sexy!” exclaimed Nicola Brognano while describing Blumarine’s fall-winter 2021-2022 collection. The 32-year-old Italian designer, tasked with reviving the brand founded by Anna Molinari, delivered garments adorned with crystals reminiscent of Britney Spears, candy-colored jackets, and Christina Aguilera-inspired corsets. Unexpectedly, however, Brognano also revived the problematic attitudes of two decades ago, when derogatory terms like “fat,” “druggie,” or “slut” were hurled at women by tabloids—a toxic culture epitomized by films like “Mean Girls,” where Lindsay Lohan came of age. “These narratives have shaped our current perspective on collective social behavior, determining who seems like a bad person and who seems good. This judgment is particularly harsh when applied to women, who have always been measured by a much crueller standard,” explains American transgender writer Jude Ellison, author of “Trainwreck: The Women We Love to Hate, Mock, and Fear… and Why” (Melville House, 2016), a book delving into the deeply misogynistic period.

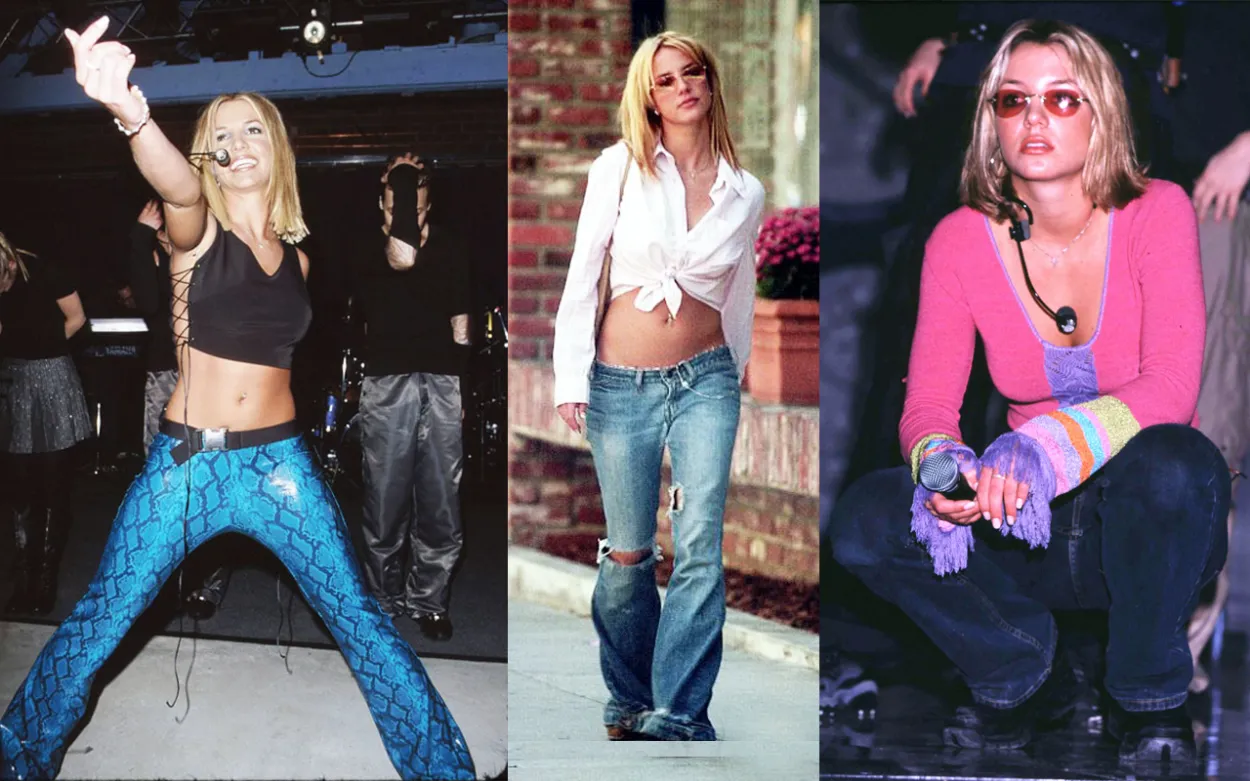

The Forgotten Years of Feminism: Unraveling the Y2K Era

The Y2K era is often dubbed as the forgotten years of feminism—a decade marked by the public stoning of young women who simply wanted to enjoy themselves. They were labeled as “bimbos,” an antiquated derogatory term for attractive but intellectually lacking women, frivolous and unconsciously behaving. These were the likes of Paris Hilton and her sister Nicky, former Disney princesses such as Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera, heiresses like Nicole Richie, or rising stars like Mischa Barton and Hilary Duff. Their stage was one of relentless scrutiny and persecution, fueled by a mainstream media that embraced a policy of escapism following the 9/11 attacks and the burgeoning blogosphere, which birthed digital outlets dedicated to mockery and ridicule that their male counterparts did not receive. Recall the image of Chenoa, cornered at her doorstep, tearful and clad in tracksuits—a moment of private pain turned into public spectacle because David Bisbal had left her. In late 2020, she posted a selfie wearing a cropped T-shirt and the same low-rise flared jeans she wore to the first casting of “Operación Triunfo” (the Spanish version of “American Idol”). Those who fail to exorcise their demons either choose not to or cannot, as some still bear the scars.

The Paradox of Centennials: Embracing a Complex Revival

Ironically, the centennials driving this revival seem oblivious to the misogynistic terror of those days. Yet, given their sociopolitical sensibilities, it’s surprising that members of Generation Z are the ones championing the Y2K flag. However, this can be understood—extrapolating the aesthetic while ignoring the ethics of a tumultuous era is a task that only the first generation of digital natives could undertake. Partly because reviving such violent values during a time of social awakening can only be done by those steeped in woke culture. There’s also the moral justification of sustainable consumption and even racial reparations, suggesting that the early 2000s style of crop tops, low-rise pants, and bling-bling accessories was, in fact, an expression of original identity by young African-American women, elevated by figures like Beyoncé, TLC, En Vogue, or Brandy. Regardless, tracking this trend has never been easier than this season, with celebrities like Rihanna, Hailey Bieber, or Rosalía embracing it on red carpets, and designers like Casey Cadwallader’s millennial Mugler, Fausto Puglisi’s revamped Roberto Cavalli, Bruno Sialelli’s new Lanvin, and others incorporating it into their collections. The Y2K effect is here to stay, as affirmed by the persistence of brands like Blumarine, Emporio Armani, Fendi, and Miu Miu, extending the impact of their celebrated micro-skirt suits into the realm of country clubs. In this, there is consensus: the Y2K trend is far from fading away.